Post

by: Rebecca Massie Lane

Director

"The

Christmas Pudding"

English

Traditional

Into

the basin

put

the plums,

Stir-about,

stir-about,

stir-about!

Next

the good

white

flour comes,

Stir-about,

stir-about,

stir

about!

Sugar

and peel

and

eggs and spice,

Stir-about,

stir-about,

stir-about!

Mix

them and fix them

and

cook them twice,

Stir-about,

stir-about,

stir-about!

The

artist, Frederick Stuart Church — often known in art as “the other Church” as

to separate his identity from the more well-known Hudson River School painter

— painted the holiday subject, “Cold Sauce with Christmas Pudding.”

Born

in Grand Rapids, Mich., Church was directed by his parents toward a business

career, and worked from age thirteen to 17 for the American Express Co. in

Chicago. His interest in drawing was not encouraged by formal training at this

time. When the Civil War broke out, he served for three years in the Union

artillery, and then returned to Chicago where he studied at the Chicago Art

Academy with artist Walter Shirlaw.

In

1870, he moved to New York and studied at the National Academy of Design with

Lemuel Wilmarth and at the Art Students League. Early on, he earned his living

as a commercial artist including illustrations for Harper's Weekly and later

for Frank Leslie’s Weekly, Century Magazine, and Ladies’ Home Journal.

A successful

New York illustrator at the height of the 19th century, Church’s work embodied

the Victorian taste for the whimsical, for images of animals and fashionable

young ladies, and for sentimental subjects.

Fanciful images of animals populated this work,

and his interest in bears was particularly pronounced in his winter subjects

such as the painting now on view at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts.

Titled “Cold Sauce with Christmas Pudding,” the painting captures the qualities

of Victorian sentimentality.

Church

often visited Barnum and Bailey's premises in New York City, as well as the

Central Park Zoo, to study and make sketches of the animals held there. He also

made painting expeditions to the countryside. In one period, he lived on a farm

and taught the owner's two young daughters to draw. His patron, the banker

Grant B. Schley eventually provided Church with a specially built studio at

Schley's estate Froh Helm, located at Far Hills, N.J.

The

museum’s painting shows a fashionably

dressed young woman, complete with elaborate bonnet, in conspiracy with a

benign, jolly bear, making (and tasting) snow-icing for a Christmas pudding.

The bear holds a bowl of sugary icing sauce, licking his paw, while the lady

holds a spreading knife that also drips the sweet sauce. The pudding is the

round bomb-shaped ball on the platter. A family of rabbits helps to support the

great weight of the pudding on platter, the taller ones peeking over the edge

in anticipation of the coming feast. In the left corner, two adolescent rabbits

have snitched pieces of curled sugar cane, and two sparrows pick up the tasty

nibbles that have dropped on the snow.

Though

we get the general idea of this painting today, perhaps we can’t fully

understand the Victorian enthusiasm for the subject because Christmas pudding

has virtually disappeared from the menus of modern life.

What

is a Christmas pudding? In Victorian England and America, it is a boiled

dessert comprised of flour, sweet dried fruits, sometimes called “plum pudding” that is cooked for hours. It dates back to

medieval times, and until the 19th century, was cooked in a pudding cloth

immersed in water. The Victorians developed a new pudding cooking technique,

placing it in a basin and steaming it. It was reheated before serving, and iced

with warm brandy, which was ignited as part of the dramatic presentation of the

pudding. After the brandy fire ebbed,

the pudding would be served with a variety of possible sauces, including lemon

cream, rum butter, custard, or sweetened béchamel.

To

the Victorians, Church’s “cold sauce” enjoyed by the animals would have been

the height of hilarity. The very idea of a bear assisting in its preparation

and a lady dressed in finery icing the finished delicacy was a wonderful joke.

As

an illustrator, he was often called upon to create appropriate holiday images

for publication, including Halloween, Thanksgiving and Christmas. He

illustrated the 1878 New World publication entitled “Out of this World”,

portraying the human and animal protagonists of each of Aesop’s fables as well

as the 1881 edition of “Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings: The Folk-Lore

of the Old Plantation,” by Joel Chandler Harris, published in New York by D.

Appleton and Co.. He was a member of the National Academy of Design.

In the same year that he painted “Cold Sauce,”

Church also created an etching for the Harper’s Weekly Children’s edition,

referencing Christmas pudding. This

illustration was accompanied by John Kendrick Bangs’s poem, “The Christmas Pudding.”

A Fairy small told me,

Over the frosty snow and rime

Is a rich plum-pudding tree;

A pudding-tree so large and

fine,

That never a day doth pass

That dozens of puddings and

pies divine

Don't fall on the soft green

grass.

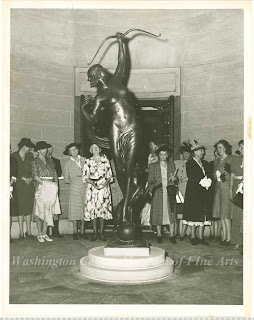

"Cold Sauce with Christmas Pudding" is on view now in the WCMFA's lobby. It was through the inventory process that the inventory team was able to easily select a work of art fitting for the holiday season.

copy.jpg)